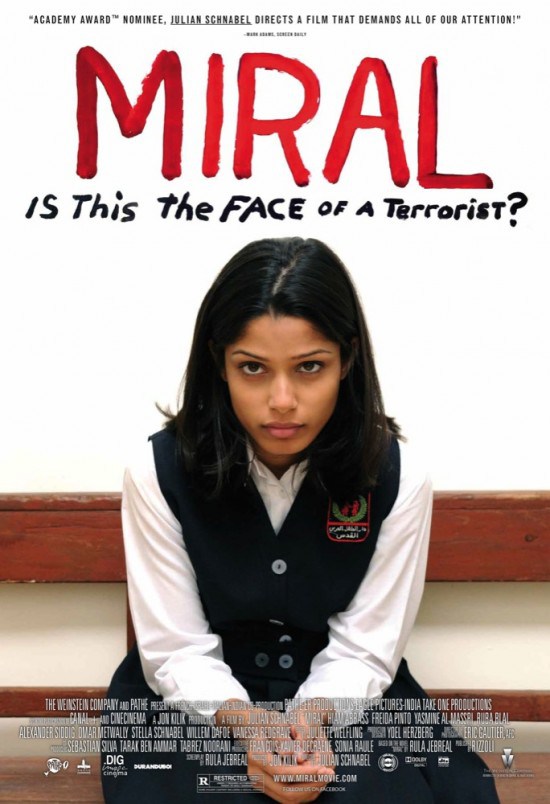

Miral, based on Rula Jabreal’s autobiographical novel of the same name, details the struggle, the suffering and the hope of the Palestinian people. Some who see the film will see little but anti-Israeli propaganda, a curious accusation when the film is directed Julian Schnabel. Or perhaps the accusation is not so curious precisely because the film is directed by Julian Schnabel. It is worth mentioning that Jabreal also happens to be Schnabel’s girlfriend in real life.

The protagonist Miral begins the film by saying that her story begins much earlier with the birth of the Israeli state and the personal crusade endured by Hind Husseini (a superb Hiam Abbas) who began Dar El Tifl, a school for abandoned Palestinian girls whose only recourse is to wither away without the aid of heroines like Hind. There is Miral’s mother Nadia, an abused young woman who flees the horrors of being sodomized daily and becomes a belly dancer who lands in prison for slapping an Israeli woman. There she meets Fatima, a former nurse sentenced to three life sentences for attempting to blow up a movie theater as an act of rebellion against the Israeli occupation. Finally, Miral Shahin is born, but her mother cannot bear the pain of living and she drowns herself, leaving Miral to her doting father who raises her with the help of Hind and Dar El Tifl. Miral, we soon discover, is not like the other girls. And then, at the same time, she is too much like the other girls.

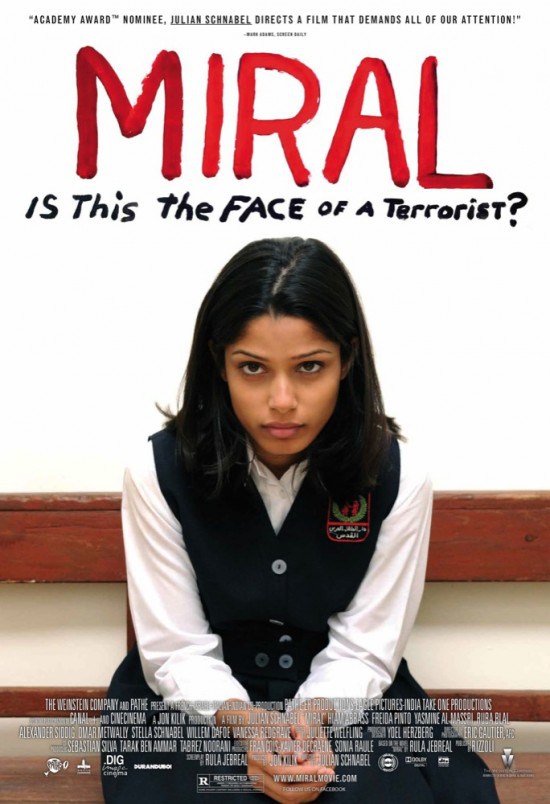

The tagline of the movie has doe-eyed Freida Pinto (Slumdog Millionaire’s Latika) dressed up in a school girl’s uniform sitting on a bench and asking, pointedly, Is This the Face of a Terrorist? The answer, we all know, is an impossible one to conjure, no matter what your position on the existence of a Palestinian state may be. Like so many other recent films about those who commit acts of violence in the name of a political cause or religion (like Paradise Now, Santosh Sivan’s The Terrorist, and Mani Ratnam’s 1998 surreal masterpiece Dil Se), the filmmakers know that such stories make us uncomfortable because they force us to think (or at least attempt to think) from the perspective of another human being whose humanity has been denied by the global collective (remember that “Philistine” is still synonymous with “barbarian” and “offensive”). Once we do that, we begin to wonder what drives people to blow themselves up for their forsaken communities or outside abortion clinics. We may wonder, does this mean George Washington was a “terrorist”? Can anyone who ever lifted a weapon in the face of oppression be defined as a terrorist?

Schnabel isn’t interested in answering the questions his movie poses. Rather, it just wants to ask the questions, throw them out into the world, and maybe perhaps have some semblance of peaceful introspection returned in hand. Is Miral a terrorist? Is she a patriot? Is she both? Is she something else altogether? Or, perhaps, she is a casualty, like millions of others born in strife, routinely degraded and dehumanized, whose only wish is to be validated, to be seen as whole, to be looked upon in the fullness of their humanity, and to be included with the rest of the human race.

Some reviewers have remarked that the strangest moment in the film comes when Miral and her revolutionary lover Hani are reunited and – in the midst of an intense makeout session – begin to espouse hope for the future of their nations and the possibility of co-existence with Israel. Yes, it is a bit jarring, but when one steps back and looks at the totality of their reality, it actually makes sense: the establishment of a Palestinian state is the overriding sentiment of their lives – greater even than that of all-important Love – and around this central idea do all the other moments and movements in Life occur. As such, the moment of reunion between Miral and Hani makes perfect sense – it isn’t romantic and it isn’t a magical movie kiss a la Lady & the Tramp, but in the context of Miral’s struggle, it is entirely plausible.

In the end, the film is really about Love: Love for one’s country, for a cause greater than oneself, for one’s family and cherished ones, and for all of humanity. Such all-encompassing and idealized humanism may sound trite and even overly sentimental, but Schnabel is able to lift much beauty out of the barrenness of the Israeli-Palestinian landscape and its undying conundrum, both literally and figuratively. As Palestinian Miral asks Lisa, her cousin’s Israeli girlfriend, “How can you love an Arab man?” Lisa’s plaintive reply? “How can I not?”

Indeed.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Photo Credit: Pacific Coast News

Photo Credit: Pacific Coast News